If Barry Neufeld Was Charged with Murder, His Case Would have Been Dismissed Over 5 Years Ago Due to Delays. See Supreme Court of Canada's R. v. Jordan ruling

Barry Neufeld Fined $750,000 by BC Human Rights Tribunal

protecting childhood innocence

Barry Neufeld

A Brief History of Barry Neufeld's Human Rights Case

Here is the saga of my 6 years of persecution by the Human Rights Tribunal. It was on October 23, 2017 that I made a public statement on Facebook:

“Transitioning Children was Child abuse.”

In December 2017, the Chilliwack CUPE 411 local publicly announced that their lawyer was filing a human rights complaint, alleging that Barry Neufeld AND the Chilliwack School District had created a unsafe work environment for some of their members.

After the media sensationalized the story (guilty until proven otherwise), the union officially filed the complaint in February 2018.

In April 2018, the Chilliwack Teacher’s Association (CTA), a local of the BCTF, filed a similar complaint, but this time solely against Barry Neufeld.

The Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms (JCCF) offered to represent Neufeld, and he signed a retainer agreement with them. They assigned James Kitchen as his lawyer.

However, in a surprising turn of events, the British Columbia Public School Employers’ Association (BCPSEA) stepped in, asserting that Neufeld, as a trustee, was covered by indemnity insurance. They agreed to cover his defense costs and appointed indemnity lawyers for me.

The JCCF subsequently withdrew from the case.

In November 2018, the BC Human Rights Tribunal (BCHRT) called for mediation. Present at the mediation were CUPE representatives, their pro bono lawyer, CTA representatives with a BCTF staff lawyer, and I with my indemnity lawyers. The Chilliwack School Board was represented by staff and the board’s lawyer. My indemnity lawyers made a compelling case, defending my statements as reasonable.

The mediation took place in separate rooms with Tribunal member Emily Ohler shuttling between the parties throughout the day in search of common ground. By the end, Ohler proposed a Restorative Justice approach to resolve the matter.

Since I am a recognized leader in Restorative Justice and recipient of the Premier’s Award in 2008 for my work in this field, welcomed the proposal.

I explained that Restorative Justice begins with three core questions:

Who has been harmed?

What are their needs?

How can we make things right?

My legal team asked, "Yes, who has been harmed? What are their names?"

Ohler responded that the unions would not provide names, claiming the victims were too terrified to come forward because they feared being “outed.”

In the spring of 2019, the CTA filed an amended complaint.

Over the next few years, little happened, so my lawyers applied to the BC Supreme Court to quash the human rights complaint. However, just before the hearing, one of the lawyers was seriously injured in a car accident, and the case was adjourned for over a year.

Meanwhile, CUPE grew frustrated with their activist pro bono lawyer and replaced her with their union staff lawyer, who proposed a settlement with the Chilliwack School Board. On October 5, 2020, the board convened an in-camera meeting with their board lawyer to discuss the settlement offer.

I attended the meeting but was asked to leave due to a perceived conflict of interest. But I refused, stating, “I am an elected member of the board, and I will not leave.” Ultimately, the board settled with CUPE by issuing a public apology, donating $5,000 to an LGBTQ+++ charity, and agreeing to attend a transgender issues training session. I abstained from voting on the matter.

In February 2021, Trustee Carin Bondar’s partner, Peter Lang, filed an application with the Supreme Court to remove me from office under Section 58 of the BC School Act, claiming that I had been in a fiduciary conflict of interest during the in-camera meeting where the CUPE settlement was discussed.

With lawyer Paul Jaffe’s help, I won the case, providing evidence that I was covered by BCPSEA’s indemnity insurance. Although I was awarded only $10,000 in compensation, Lang’s legal fees were covered by the BC Federation of Labour.

In the summer of 2023, my lawyers finally secured a hearing before the Supreme Court. The judge approved the CTA’s amended 2019 complaint but declined to quash the BCHRT complaint, calling it “premature.” The case was scheduled to proceed in December 2023.

CUPE later announced that they would no longer participate but would abide by the CTA’s decisions moving forward. The December 2023 hearing was postponed to June 17, 2024.

In January 2024, my lawyers informed me that the CTA had made an out-of-court settlement offer, requesting:

A public apology.

A promise to never run for public office again.

Participation in a reeducation program.

A $50,000 donation to an LGBTQ+ charity.

My lawyers argued that this was a favorable offer, as I risked being found guilty of hate speech if the case went to a full hearing. They also reassured me that the indemnity insurance would cover the $50,000 donation.

I considered the offer carefully. I revised the apology, removed #2 & 3, and searched for an LGBTQ+ charity that would not encourage children to harm their bodies. Ultimately, I rejected the offer entirely. Because I stood my ground for 6 years, Giving in would not protect children from harm. This was not about my Charter Rights or Free Speech: it was about protecting vulnerable children.

Shortly thereafter, I received a letter from the indemnity insurance company informing me that, because I had rejected what they considered a very reasonable settlement, they would no longer cover my defense costs. In March 2024, I began searching for new legal counsel.

The indemnity lawyers offered to continue representing me for a $150,000 retainer.

In the meantime, the BCHRT and CTA lawyers increased the pressure on me with document demands, conference calls, and deadlines. I kept searching for legal counsel, but I was turned down by both the JCCF and Freedoms Advocate after they reviewed the case files. The Democracy Fund did not respond. Paul Jaffe was not available: he was busy defending pastors against COVID infractions.

Due to my lack of legal representation, the BCHRT adjourned the June 17, 2024 hearing to July 4. I appeared with only Kari Simpson as lay counsel. I was grateful there were about 20 of my supporters in the room. The remainder of the hearings were postponed until October 21, for a two-week trial.

The CTA has three anonymized witnesses (school employees who "don’t feel safe"), one expert witness (Dr. Elizabeth Saewyc), former CTA president Ed Klettke, and former BCTF President Glen Hansman.

Kari and I and my supporters began meeting via Zoom on Thursday evenings to strategize.

After months of not being able to find a lawyer who would take my case (except for the ones who wanted more than I could ever pay or ask people to donate towards), I finally got connected again with James Kitchen, who now has his own practice.

According to Kitchen’s website, his “dedication lies in fiercely defending human rights and individual freedoms” and he has earned a reputation as a skillful Christian lawyer. He estimates that the cost for defense would be approximately $60,000. His first step will be to ask for another adjournment to properly prepare for the hearing. The Teacher’s Union will NOT be happy with this, for in six years, they have amassed hundreds of files against me.

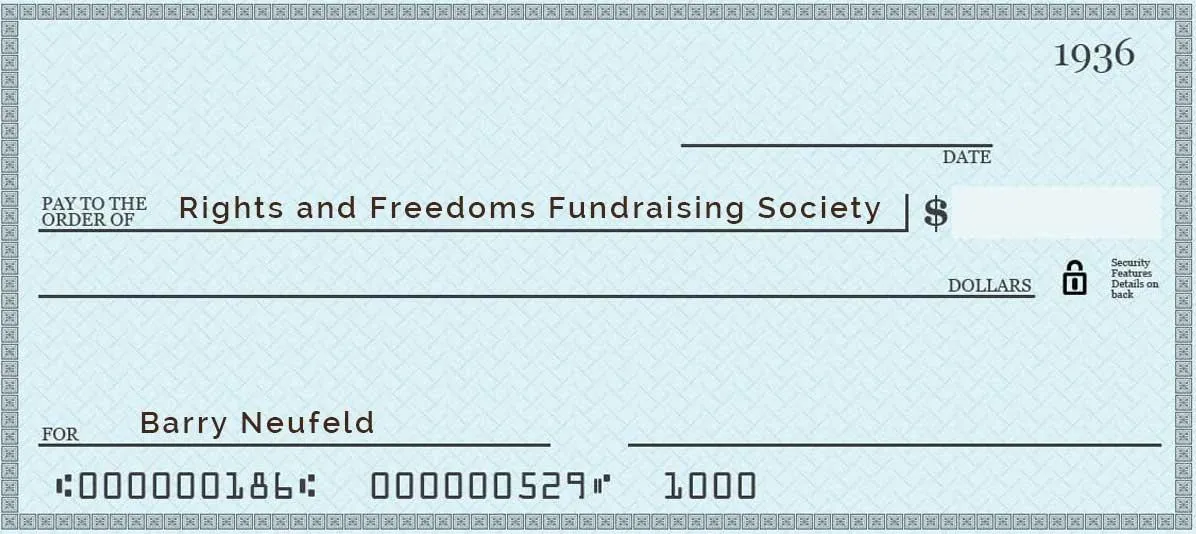

I am pleased to announce that the Rights and Freedoms Fundraising Society has agreed to assist me (and other worthy freedom fighters) to raise funds for my defense.

Donate to Barry Neufeld's Case

Donate By Mail

Attn: Barry Neufeld

c/o Rights and Freedoms Fundraising Society

P.O. Box 21004

Chilliwack, BC V2P 8A9

Barry Neufeld News and Case Updates

James Kitchen Responds to Commissioner’s Attempt to Subvert the Legal Process

Letter From B.C.’s Office of the Human Rights Commissioner

NOVEMBER 15, 2024

B.C. Human Rights Tribunal 1270 – 605 Robson Street Vancouver, BC V6B 5J3

Attn: Britt S., Case Manager

Re: British Columbia Teachers Federation obo Chilliwack Teachers Association v. Barry Neufeld, HRT Case Number CS-01372

Please find enclosed a document book of academic articles that the Commissioner intends to rely on in her written submissions, given that we are now unable to call Dr. Travers. These outline the formation, effect and rhetorical work of moral panics, including discussion of the claim that gender affirming care or support is child abuse. We consider that these articles reflect social fact, and the Tribunal can take notice of their content given its specialized knowledge in assessing claims under s. 7 of the Code and whether or not speech is discriminatory or amounts to hate speech.1 However, for the benefit of transparency, we are providing notice and copies to all parties well in advance of the deadline for our written submissions.

Sincerely,

Maria Sokolova Staff Lawyer

B.C.’s Office of the Human Rights Commissioner

James Kitchen Responds...

JAMES SM KITCHEN

Barrister & Solicitor

203-304 Main St S, Suite 224 Airdrie, AB T4B 3C3

587-330-0893

November 18, 2024

VIA EMAIL

BC Human Rights Tribunal 1270 – 605 Robson Street Vancouver, BC V6B 5J3

Attention: Devyn Cousineau, Tribunal Member Robin Dean, Tribunal Member Laila Said-Alam, Tribunal Member

Dear Panel Members:

RE: BCTF obo CTA v Barry Neufeld, BCHRT Case No. CS-001372—BC Human Rights Commission’s Proposed Opinion Evidence

This submission responds to the BC Human Rights Commission’s effort to enter opinion evidence in the absence of an expert witness, as well as its single argument for doing so. The Commission relies on Sarah Blake’s Administrative Law in Canada, 7th ed (LexisNexis Canada, 2022) at §2.14, citing no particular pinpoint.

The starting point is that the Tribunal’s expertise is in discrimination. The Commission’s assertion that the Tribunal may take notice of “the formation, effect and rhetorical work” of moral panic “given its specialized knowledge in assessing claims under s. 7 of the Code” is a bait-and-switch, and moreover, a self-defeating argument. The Tribunal’s expertise in assessing discrimination claims would lend it no particular expertise in assessing moral panic, and its presumed lack of expertise in this social science subject area would admit of need for expert guidance by way of an expert witness. On the other hand, had the Tribunal specialized expertise in the area of moral panic, it would not require a surfeit of material on the subject in order to divine the presence or absence thereof.

Moving to the administrative law textbook on which the Commission relies for its proposition, Ms. Blake’s remarks alternate between truisms and circumstances that bear little resemblance to this particular matter. Beginning with the second paragraph, it is unclear what “lay people…not schooled in the rules of evidence” to which Ms. Blake refers, but certainly her characterization does not apply to this panel, the legal acumen of its members combining to bring practical experience in eight distinct areas of the law to their present appointment.

That a panel of this particular proficiency should require 23 articles exploring the topic of moral panic in order to reach a conclusion as to whether discrimination has occurred seems improbable. Accepting such a superfluous volume of unqualified opinion material would stray far outside the central purpose of the inquiry—a practice Ms. Blake would seem to discourage: “As the most important evidence is that which concerns the key facts on which the decision will turn, the key factual issues should be identified so as to avoid straying too far from the central purpose of the inquiry”.

Ms. Blake continues to the effect that the purpose of admitting evidence is “to keep the hearing focused on the matters to be decided”. Indeed, the Tribunal should have regard to “[t]he purpose and subject matter of the proceeding described in the notice of hearing or in a statement of the allegations”. This seems uncontroversial. It is also the reason the Respondent objects to the admission of 450 pages of gratuitous scholarship focused on moral panic, let alone in the absence of an expert witness who might be cross-examined on its contents.

The administrative law text on which the Commission relies does not make the case the Commission claims. The following summarizes the text’s thrust:

· While “[a] tribunal may use its own expertise to assess whether to accept or reject [an] opinion”, there is no reason to believe such an opinion is to be admitted without an expert in tow;

· While “[a] tribunal may take notice of commonly accepted facts and generally recognized facts within its specialized knowledge”, there is no reason to believe a tribunal may take notice of “facts” outside its specialized knowledge;

· Even where “[a] tribunal may take notice of commonly accepted facts and generally recognized facts within its specialized knowledge…a tribunal should not rely on its ability to take notice of common facts as the basis of its finding on an important disputed fact”;

· While “[e]xpertise may assist a tribunal in drawing inferences from primary facts…the expertise of the tribunal should not be the basis of an essential finding of fact upon which a decision turns”.

While the Morgan Criteria of the R v Find1 epoch—facts so notorious or generally accepted as not to be the subject of debate among reasonable persons or facts capable of immediate and accurate demonstration by resort to readily accessible sources of indisputable accuracy—are no longer the single standard for “judicial” notice in all circumstances, they continue to apply strictly where such “facts” are positioned proximate to the issue in dispute and its disposition.2 The Commission’s statement, “These outline the formation, effect and rhetorical work of moral panics, including discussion of the claim that gender affirming care or support is child abuse” admits of such proximity; accordingly, the Morgan Criteria would apply to oust judicial notice of the social facts in question, which are obviously in dispute and upon which reasonable people are wont to disagree. Such facts, even social facts, would need to be proven.

The Tribunal can tell whether or not there is discrimination quite apart from whether or not moral panic occurred. Put another way, the point of the exercise is not to assess whether moral panic happened, rather whether discrimination happened. Since there is no reason to believe “moral panic” is either sufficient or necessary for the occurrence of discrimination, the Tribunal cannot be assisted by opinion on the topic, with or without an expert. Moreover, attempting to foist the accusation of moral panic on the Respondent crosses the line between finding fact and projecting a caricature.

The Respondent therefore opposes the admission of the Commission’s proposed opinion evidence.

In the event the Tribunal rules the Commission’s proposed social fact evidence admissible, the Respondent will enter a not insubstantial amount of social fact evidence to counter the materials proposed by the Commission. The admission of such a prodigious quantity of written opinion evidence absent an expert would compel the Respondent to enter an equal volume of scholarship defeating the proposition. “Social ‘facts’” are, after all, in the eye of the beholder.

Regards,

James SM Kitchen

Barrister & Solicitor Counsel for Barry Neufeld

Stay Informed

Stay informed with the latest updates on our cases, research and events.

©️ Copyright 2026 Rights and Freedoms Fundraising Society. All Rights Reserved.